Complementing Python With Rust

I gave a talk the other day at Python meetup in Stockholm with the same title. I wanted to also put it online as a post in case anybody is interested in using Rust from Python. (If you fancy watching a video instead, scroll to the bottom).

I like working with Python. I have been working with it for a few years building web-applications. It is an expressive language, there are libraries for almost everything I need, it is quick to try out ideas or to build features and I feel productive.

However, for critical paths in applications, Python is not a great fit. These paths could be parts of code which are executed very often or which need to be as quick as possible. For example, Jinja2 is a very popular templating library in Python. In turn, Jinja2 depends on MarkupSafe. In order to make escaping strings as fast as possible, the functionality is implemented in C.

This has also been the recommended approach to solving performance problems in Python — to write C/C++ extensions. However, low level languages like C/C++ don’t provide any safety to the programmer and this many times leads to vulnerabilities like Heartbleed or Ghost. These exploits were due to buffer overflow. These exploits also happened in a very widely deployed codebase. The point is, it is quite hard to manage memory properly when there is no support from the language.

Rust is an open source, modern, systems programming language sponsored by Mozilla. It is sponsored by Mozilla in the sense that, several of the core contributors are employees of Mozilla and work full time on Rust. The language grew out of a personal project by Mozilla employee Graydon Hoare and was first announced in 2010. V1.0 was released in May 2015, and there is a new release every 6 weeks. I consider Rust as a young teenager (or maybe just-starting-school) bringing fresh ideas to programming languages. It probably moved out of infancy when companies started using it in production.

Of the several features that Rust has, I find 3 are particularly relevant to building Python extensions using Rust — zero-cost abstractions, minimal runtime and guaranteed memory safety.

Zero cost abstractions is something Rust borrows from C++.

C++ implementations obey the zero-overhead principle: What you don’t use, you don’t pay for. And further: What you do use, you couldn’t hand code any better

So this language principle would mean that, for features of the language that I don’t use, there should be no penalty. For features of the language that I do use, it shouldn’t be possible to do any better by going down in the stack (i.e. by writing generated machine instructions, for example). One obvious evidence of this is in the trait implementation. Traits is one of the cornerstone’s of the abstraction model in Rust. It allows us to add behaviour to types in a variety of cases. But the design principle and the implementation of this feature guarantees that there is no penalty/overhead for using Traits. See this excellent post for details.

Minimal runtime ensures that there is no overhead when we run our code. For example, in a dynamic language, the runtime determines where the method should be dispatched. In a language with garbage collection, the runtime would have to periodically stop execution while the garbage collector runs. The minimal runtime of Rust guarantees that the program will not suffer this overhead.

Guaranteed memory safety means that the program only accesses memory that belongs to it. It shouldn’t be possible to write past this memory or access it after it has been released. Also, remember that there is no garbage collector in Rust. So in this case, the language constructs need to ensure that these guarantees are fulfilled. It is solved in Rust using ownership and borrowing.

With that background, let us get a flavor of Rust by writing a hello-world application. I use rustup to manage my Rust versions. Cargo is the build manager of choice for Rust programs, similar to npm for JavaScript.

$ rustup show

Default host: x86_64-apple-darwin

installed toolchains

--------------------

stable-x86_64-apple-darwin

beta-x86_64-apple-darwin

nightly-x86_64-apple-darwin (default)

active toolchain

----------------

nightly-x86_64-apple-darwin (default)

rustc 1.15.0-nightly (daf8c1dfc 2016-12-05)

# create a hello-world binary

$ cargo new hello-world --bin

$ cd hello-world

$ tree

.

├── Cargo.toml

└── src

└── main.rs

1 directory, 2 files

$ cargo build

Compiling hello-world v0.1.0 (file:///private/tmp/hello-world)

Finished debug [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 3.30 secs

$ cargo run

Finished debug [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.0 secs

Running `target/debug/hello-world`

Hello, world!

Let us now create a hello-world of a Rust extension that we can call from Python. I will use the cffi package in Python to interface between the two languages.

$ cargo new double

$ cd double

$ virtualenv .env

$ . ./.env/bin/activate

$ pip install cffi

$ cargo build

$ python double.py

6

$ cat Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "double"

version = "0.1.0"

authors = ["Pradip Caulagi <caulagi@gmail.com>"]

[dependencies]

[lib]

name = "double"

crate-type = ["dylib"]

$ cat double.py

from cffi import FFI

ffi = FFI()

ffi.cdef("""

int double(int);

""")

C = ffi.dlopen("target/debug/libdouble.dylib")

print(C.double(3))

$ cat lib.rs

#[no_mangle]

pub extern fn double(n: i32) -> i32 {

n * 2

}

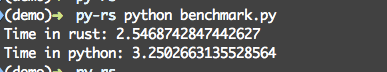

Finally, to show you the difference in performance,

I will consider the following problem — I want to read a text file,

split it into words on whitespace, and find the most common words in

that file. This is useful, for example,

in writing a spelling-corrector. It

is simple to do this in Python since it has a built in

data structure. collections.Counter is a kind of dictionary and

has a method called most_common, that returns the common words

with their count. Rust doesn’t have this method. So we will write an

implementation of most_common that takes a dictionary (HashMap in Rust)

as input and returns the most common key after aggregating.

$ cargo new words

$ cargo build --release

$ cat benchmark.py

import os

import re

import time

from cffi import FFI

from collections import Counter

ffi = FFI()

ffi.cdef("""

int most_common(const char *, int);

""")

C = ffi.dlopen("target/release/libcounter.dylib")

def benchmark_rs(path, n=10):

path = bytes(path.encode('utf-8'))

start = time.time()

C.most_common(path, n)

return time.time() - start

def words(text):

return re.findall(r'\w+', text.lower())

def benchmark(path, n=10):

start = time.time()

with open(path) as fp:

Counter(words(fp.read())).most_common(n)

return time.time() - start

if __name__ == "__main__":

time_rs = time_py = 0

base_dir = 'data'

for f in os.listdir(base_dir):

path = os.path.join(base_dir, f)

time_rs += benchmark_rs(path)

time_py += benchmark(path)

print("Time in rust: %s" % time_rs)

print("Time in python: %s" % time_py)

$ cat Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "words"

version = "0.1.0"

authors = ["Pradip Caulagi <caulagi@gmail.com>"]

[dependencies]

libc = "*"

[lib]

name = "counter"

crate-type = ["dylib"]

$ cat lib.rs

extern crate libc;

use std::clone::Clone;

use std::collections::HashMap;

use std::ffi::CStr;

use std::fs::File;

use std::hash::Hash;

use std::io::Read;

use std::str;

use libc::c_char;

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn most_common(c_buf: *const c_char, n: i32) -> i32 {

let buf = unsafe { CStr::from_ptr(c_buf).to_bytes() };

let path = str::from_utf8(buf).unwrap();

bucketize_words(path, n as usize)[0].1 as i32

}

/// Read the file indicated by path and return the most common

/// words in the file along with number of occurences

fn bucketize_words(path: &str, n: usize) -> Vec<(String, usize)> {

let mut f = File::open(path).unwrap();

let mut data = String::new();

f.read_to_string(&mut data).unwrap();

let mut bag = HashMap::new();

for item in data.split_whitespace() {

let count = bag.entry(item.to_lowercase()).or_insert(0);

*count += 1;

}

n_most_common(bag, n)

}

/// Find the most common words in the bag based on number of occurrences

fn n_most_common<T>(bag: HashMap<T, usize>, n: usize) -> Vec<(T, usize)>

where T: Eq + Hash + Clone

{

let mut count_vec: Vec<_> = bag.into_iter().collect();

count_vec.sort_by(|a, b| b.1.cmp(&a.1));

count_vec.truncate(n);

count_vec

}

$ python benchmark.py

Before I show the difference in numbers, I want to take a moment to talk about the method signature in Rust.

/// Find most common words in

/// the bag based on number

/// of occurrences

fn n_most_common<T>(

bag: HashMap<T, usize>,

n: usize) -> Vec<(T, usize

)> where T: Eq + Hash + Clone

So the n_most_common method takes a HashMap (dictionary) as the

first argument. The key in this HashMap is a generic type T but the where

clause specifies that this generic type T has to implement 3 traits — Eq, Hash

and Clone. This is exactly same in a Python dictionary, where the keys have be

hashable. But in the case of Rust, this is checked at compile type and doesn’t

need unit-tests for this behaviour to hold.

Time taken in Rust and Python (lower is better)

Time taken in Rust and Python (lower is better)

As for the difference in performance, I used the same file that was used in the original article. Make 3/4 copies of this file and put it in ‘data’ directory (the file names don’t matter).

My take aways from this exercise are — types in Rust are awesome and it is relatively easy to move code from Python to Rust when performance matters.

Something I didn’t explore was to check if the benefits will be much higher for concurrent code.

There are a few talks that I borrowed ideas from — here, here and here. The first talk takes a different approach and uses rust-cpython for binding Python and Rust.

You can also watch a recording of the video, but if you have already read so far, there is nothing new in the video. I start at 3 mins.